The 3 Types of Investors

Few topics are as mysterious as investing. Investing has had an especially prominent place in the American story, being intimately connected with the idea of being “self-made.” But like all legends, reality can be disconnected from perception. Investing is one of the most misunderstood and controversial money concepts, in spite of (or perhaps because of) the abundance of information available on the topic.

One of the reasons investment recommendations may seem disparate and confusing is that there are fundamentally different approaches to investing. Benjamin Graham described the three primary types of investors almost 70 years ago in his foundational book, The Intelligent Investor, and these three are still the main categories today. Understanding what type of investor you are (and should be) will help you know what investment advice to tune in – and tune out.

1. The Speculator

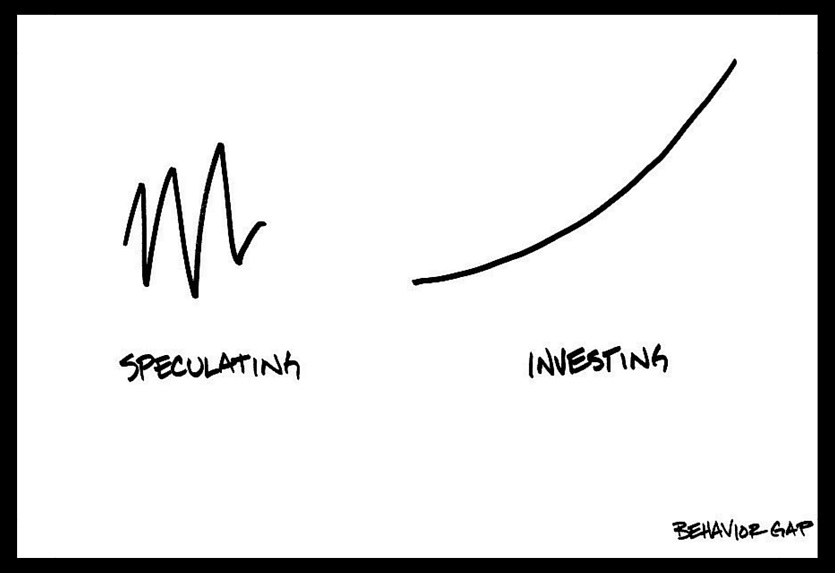

Speculators are primarily interested in making a quick buck, usually through short-term price fluctuations. They try to buy something at $50 today that they think will jump to $100 tomorrow. Speculators use tactics like day-trading, market timing, or shorting (betting something will go down). The focus is usually short term in nature and is typically a zero-sum game – in order for speculators to win, someone else has to lose.

There are two reasons I recommend you avoid speculating, one philosophical and one practical. First, speculating isn’t true investing. It’s effectively gambling using investment vehicles of stocks and bonds. It depends entirely on being able to accurately predict the future, which is nearly impossible. Not only do you need to predict the future correctly, to be a speculator you also have to be able to predict the future better than all your competitors in the market!

In true investing, you are trading your capital in exchange for ownership in a real, producing company (or loaning to one). The goal of that company is to produce something that its customers value highly enough that they are willing to pay for it. It’s the profit from this sale that rewards you as an investor, and ideally the more value your company provides (or the more efficiently it produces), the more value you receive back. This form of investing takes time, however, and speculation is an impatient game. Speculation only looks for ways to extract value out of the system.

The second reason you shouldn’t speculate is that it rarely works. Anyone can get lucky, I suppose, but as Graham says in his book, “If you speculate you will (most probably) lose your money in the end.” I’ve met hundreds of millionaires and billionaires who’ve gotten there through real investing, but I have yet to meet one personally who did it by day-trading. They are out there, but like getting rich through gambling, success is the outlier. (There are many, however, who make money selling courses teaching others to speculate.)

Speculating vs Investing, by @BehaviorGap

If speculation is what investing is not, let’s turn our attention to true investing.

2. The Defensive (or Passive) Investor

Before you skip this one based on the title, let me say it’s not what you think it is. In fact, there’s a high chance that most reading this should themselves be in this category. Graham didn’t strictly equate being defensive in the same sense that we talk about an investment portfolio being more “conservative” versus “aggressive.” Defensiveness here is referring to the need to protect capital over the long term. Retirement savings, for instance, like IRAs and 401(k)s will be very important for many retirees to live off for possibly decades. It would be inappropriate for these investors to speculate their retirement savings, making big bets on short-term swings. Depending on their personal situations, many of these retirees could still have most of their investments in company ownership, often called the “riskier” approach, but they mitigate risks in other ways.

Good defensive investors could be identified with four standard characteristics:

- They are widely diversified in their holdings.

- They pay low fees to avoid unnecessarily diminished returns.

- They aim for average returns instead of trying to “beat the market.”

- They hold a long-term perspective, over many market cycles (“buy and hold”).

When Graham wrote Intelligent Investing, his readers didn’t have the same investment vehicles available we have today, specifically the index fund. An index fund doesn’t have portfolio managers trying to pick which stocks to buy and sell. It simply adheres to a specific index that usually represents a wide part of the market. For instance, an S&P 500 index fund simply buys whatever companies are listed on the S&P 500, and it tries to track that index as closely as possible. This type of investing is called “passive”, precisely because fund managers aren’t making decisions. They’re simply following the market. And by avoiding the management overhead, index funds are also much less expensive than most traditional actively managed funds.

Index funds are often incredibly diversified. That S&P 500 fund would hold 500-ish US companies. Many hold more, possibly thousands, of companies. This approach by definition does not “beat the market” because it is effectively trying just to be the market!

“But,” you ask, “who wants to be average?” Here’s the interesting thing about this passive approach. Each year S&P Dow Jones Indices releases a scorecard grading active managers in their performance versus the standard indexes. Over the long term, the major U.S. indexes consistently beat 80% of actively-managed mutual funds investing in U.S. equities. And the top 20% who do beat their index rarely do so with a high level of consistency. Not only is it difficult for the more expensive active funds to beat their benchmark, it’s even more difficult for you as a consumer to pick the ones that will outperform before they do it!

A defensive investor still must wrestle with important considerations like:

- How much in stocks, bonds, commodities, or alternative investments?

- How much in large companies vs. small companies?

- How much in U.S. vs. international companies? International emerging markets vs. developed nations?

These decisions are important but specific to individual investors’ situation. Suffice it to say that wherever one lands, all of these options can be acquired using a passive approach.

Defensive investing is most appropriate for non-professional investors who are interested in preserving wealth over time. But what other way is there?

3. The Enterprising Investor

An enterprising investor is someone who intentionally seeks to do better than average. Graham wrote his book largely with the enterprising investor in mind. There are different tactics for going about this, such as value investing (Graham’s approach) or growth investing, but the goal is the same. If the defensive investor is out to conserve wealth, the enterprising investor is looking for ways to create wealth. Good enterprising investors are generally:

- More concentrated, less diversified than defensive investors.

- Disciplined and intentional with their methodology.

- Long-term in their perspective.

The enterprising investor is different from the speculator, because the speculator is interested in short-term price fluctuations while this investor focuses on long-term business fundamentals. The enterprising investor is different from the defensive investor, because the defensive investor buys and holds large parts of the market, while this investor tries to strategically buy and hold investments that hold greater opportunity.

The trade-off for greater opportunity, however, is more risk. By consolidating fewer eggs into one basket, the enterprising investor is hoping that their strategic reasoning will pay off in the long run. Being wrong, however, has serious consequences.

There are three ways enterprising investors approach this task:

- Stock picking. With stock picking, you select the companies that you believe have the most potential to achieve your particular investment goals. There are different strategies to determine stocks, such as “value investing” (Graham’s personal approach). Stock picking is notoriously hard, however. If it’s hard for teams of full-time, well-trained professional MBAs and CFAs to consistently beat the market, what leads you to believe you can? What unusual advantage do you have that they don’t?

- Private ventures. The stock market offers ownership in publicly-traded companies, but there are many businesses that don’t trade on the market. By investing in non-traded ventures, investors hope to capture better-than-average returns through opportunities such as real estate developments, limited partnerships, start-ups, or other businesses seeking growth capital. This approach usually takes more money to get involved in and requires a sophisticated investor to understand the risks of their particular deal. With these ventures, the only thing you control is when you get in.

- Running a business. Investing doesn’t always mean providing capital to someone else’s business. Many investors create wealth by directly starting a business or running one that they share ownership in. This could be the founder of a family-owned company or an executive with stock options in a large, public one.

Before enterprising investors start down this path, the question they need to answer is this: what unfair advantage do they have over the others in the market? What unique knowledge, experience, skill, or relationships do they have that will set them ahead of everyone else? If there isn’t a clear answer, then a more defensive route may be more appropriate.

In my opinion, running a business is the purest form of true investing. In creating a business the investor not only puts in money, they also dedicate their skills, time, and sweat-equity to produce whatever good their customers value. This is of course the hardest path, but it’s one that offers by far the greatest pay-off opportunity if done correctly.

One final illustration: it is possible to take all three approaches to investing, possibly even at once. My friend Mike is an example of this. Mike created a significant amount of wealth as an enterprising investor when he created a company, built and ran it for several years, then sold it to a larger corporation. He continues as an enterprising investor by starting another business, but he’s now become a defensive investor, growing the wealth from his business sale in a diversified portfolio. Because he has significant wealth, he even does some speculative investments for fun, but only with money that he is fully prepared to lose entirely.

The first step in being successful as an investor is understanding who you are and who you aren’t. By figuring out what type of investor you are you will avoid making unnecessary – and potentially costly – mistakes.

< Back to Updates